Heroin in our midst: Part 1

By Joshua Rosenau

HIGHLAND LAKES — Ben was 14 when he first tried heroin.

After experimenting with many different kinds of drugs, he learned he preferred prescription pain killers to most anything else. He quickly graduated to heroin.

“I was always interested in opiates,” he said. “Kids my age were trying to get pot, and I was trying to go through their parent’s medicine cabinets.”

Tess was in her early thirties and already had an active addiction with another drug when she first began using heroin. “My situation was I was working full-time. I wasn’t hanging out with other addicts. I was maintaining a lifestyle that everybody thought I should have as a 30-something woman.”

Pete first approached heroin in his late teens, only to have heroin approach him in his early twenties. “The very first time I had done heroin, was we had taken a trip down the shore... And I had done other drugs before, but I had never tried heroin,” he said.

A few years later, an injured relative and then a friend would draw the drug closer to him.

Heroin moves in

The stories of these recovering addicts show that the heroin trade has set up shop in Sussex County. Since police first recognized the presence of the drug back in the late 1990s, the trade and traffic in heroin has pushed into hundreds of homes in this rural exurb of New York City, showing no signs of weakening over roughly 15 years.

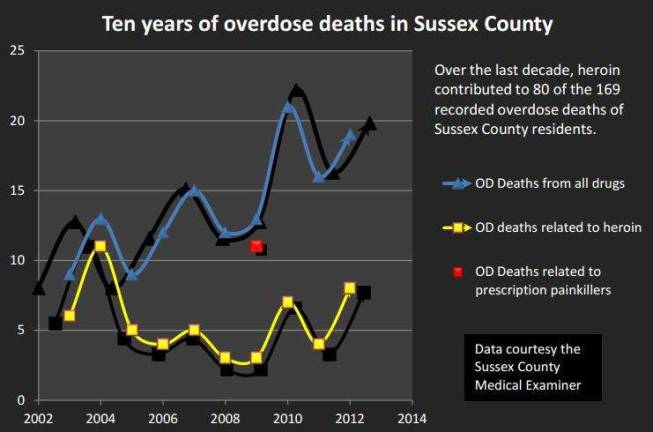

Since 2000, cheap, seductive and addictive heroin has been a factor in the deaths of 80 of Sussex County’s sons, daughters, mothers and fathers.

Many were young and addicted. Many were also likely engaged in crime. Overdoses related to heroin have killed four as of March of this year.

They are the nameless lost as the ties between Sussex and heroin trade strengthen.

Today many addicts recover, thanks to rehabilitation, therapy and pressure from the courts.

Despite being a criminal enterprise under the law, the trade in heroin is also a business venture that persists regardless of legal standing.

Tom Reed, head of the county’s drug task force, described the entrepreneurial skill of cartels that supply the Northeast with heroin produced from Columbian poppy crops.

“These guys should be teaching at the business school at Harvard,” he said.

In interview after interview, recovering addicts, therapists and police reported that heroin’s business-model is succeeding to reach customers in Sussex County and other areas surrounding New York City, because of its strong supply, cheap price, wide availability, easy use, and addictiveness.

Most importantly, there are people willing to roll the dice and try heroin, who later suffer the pain and criminal consequences of addiction.

In order to better understand heroin’s effects and the culture surrounding it, three recovering addicts offered their stories under the condition they remain anonymous.

Ben

Ben first used heroin after a friend of a friend, someone already initiated with heroin, gave him a small amount to sniff.

“So I couldn’t get access to heroin. It wasn’t like it is now, where you can get heroin out here,” he said of the time he began using the drug around 2003.

He is striking at first impression: a tall, clear-eyed, perceptive sort — far from the faded, semi-conscious person he was while he was using.

“When I was doing it, you had to go to Newark. So at 15 I’m jumping into a car going to Newark with my friends. By the time I was 19, I was a full-blown addict.”

Once dependent on the drug, Ben spent anywhere from $20 to $80 a day on heroin he then injected directly. He continued the habit, even while knowing it was unsustainable, he said.

“At maximum I was using 15 bags a day, which is ridiculous and a waste. I was using way too much. At my low as a full-blown addict I was using three to eight bags a day.

“I needed those three: One at morning, one afternoon, and one at night. But anything in between was great. In my mind, I knew that what I was doing was completely out of control. I think we can all agree, it’s not normal to wake up and need to stick a needle in your arm.”

Tess

Tess is a working professional with a history of drug abuse. She built a career. She had her own place. Then heroin came in.

She met someone who also had the appearance of being hardworking and healthy, but who she later learned was actively using heroin.

Coming home to unwind after a long day at work, there’d be heroin waiting in the living room, she said. “Me saying, ‘No, I can’t do heroin,’ that lasted maybe a few days,” she said. “I was like alright, I am trying this.”

She used heroin off-and-on for two years and saw her life go down hill extremely fast. “All of a sudden my family didn’t want to have anything to do with me.

“My friends cut me out. I didn’t have any friends that used,” she said.

Somehow, she made it into work most days.

Often, she would go home for lunch to do heroin before finishing out the day. She was also regularly in withdrawal while on the job, she said.

“I was holding on by a thread, basically,” she said. “Going to work sick, throwing up in the bathroom, I didn’t know how people didn’t find out sooner.”

She fell behind on her bills and racked up credit card debt in the hope of maintaining two lives—one as an independent career woman, the other as someone dependent on heroin.

“My whole life that I had worked to build over the years through business and non-profit work, friendships, that all started to crumble and go away,” she said.

Pete

Even though he was curious about the drug, Pete tried to keep his use under the threshold of addiction when first introduced to heroin.

“I did start to recognize the negative effects of it almost immediately,” he said. “So I did try and distance myself from it and keep it as a fun thing, not something to rely on.”

Sometime later, a close relative suffered a back injury in a car crash. Pete used marijuana and opiate pain killers with his relative.

“It was sort of a mixed bag,” he said. “Because he was in his late 30s, he didn’t know as many people, connections. I hung out with him socially. We worked together. We used to hang out and smoke pot. He’d share pills once in a while if he had extra. If I would go get some for him, he’d throw me a few.”

Sporadically, he would seek out heroin on his own. Meanwhile another friend began a more active heroin habit. One day, broke and sick from withdrawal, the friend came and begged him to drive to Paterson to buy heroin.

He agreed, but only on the stipulation that he could use some, too.

“That’s the worst part for me, because I realized that as it progressed for me over my life¬—that it went from that innocuous, carefree thing to being a sort of coping mechanism. It became like, ‘If I’m going to be surrounded by it constantly, I guess I might as well see what it’s about or at least be on the same wavelength.’

”Like what people say about other drugs: It’s really hard to be around someone who is really drunk when you’re sober. It became like that.”

The stories of these recovering heroin addicts will continue next week with an examination of law enforcement’s fight against the drug.

Editor's note

This series marks a collaborative effort between Straus News and its sources, particularly reforming addicts.

The execution of this series depended greatly on the testimony of those in recovery and, particularly, the willingness of one former heroin user.

Straus News includes this note to give due credit to those whose worth as sources and collaborators cannot be acknowledged. Thank you.

Heroin in our midst:

Part 1: Heroin is here.

Part 2: Law enforcement’s attempt to deal with the epidemic.

Part 3: Confronting addiction; do drug courts work?

Part 4: The business of hooking kids.