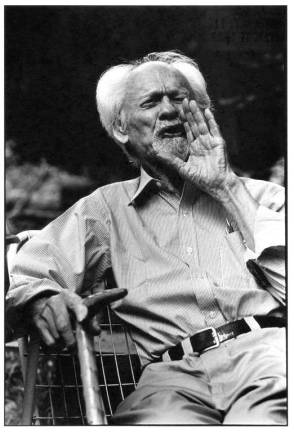

Kenneth Burke: Sage of Andover

ANDOVER — Remember Harry Chapin?

He's the popular singer and songwriter from 1970's best remembered for the classic “Taxi” and the “Cat's in the Cradle.” Chapin wrote all his own songs, except one. This is a beautiful, poetical piece called “One Light in a Dark Valley.” It was written, words and music, by Chapin's maternal grandfather, Kenneth Burke.

Burke, for over 70 years, lived on a farm on Amity Road in Andover, which his family still holds. The Chapin children used to roam and play there in the summers. Burke appears, like many great American thinkers, to have fallen from the American memory. But this literary critic, poet and philosopher was among the most influential people of his time, and his impact resonates to the present day.

He was born in Pittsburgh in 1897, went to Ohio State and Columbia universities, got a diploma from neither and eventually became editor in 1923 of The Dial literary magazine in New York City. In 1922 he purchased the property in Andover. He worked in New York. He taught various stints at a number of universities around the nation. But he considered the farm his home and always returned there. A deep reader and original thinker, his fame as a literary critic grew.

Burke “was, by many accounts, the greatest rhetorician since Cicero, which in a world of words such as ours really says something, not only about the man but about his influence on people who study language, literature, and human relations,” said David Blakesley, a professor at Clemson University, member of the Kenneth Burke Society and editor of the society's Journal.

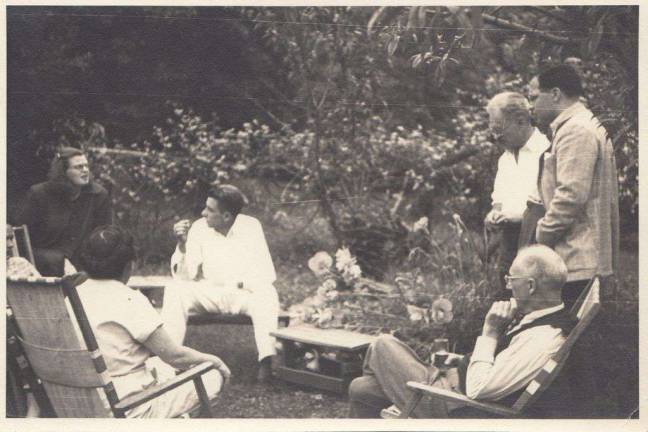

“Burke was a central figure in literary circles,” Blakesley said, “holding court (or, more accurately, chautauquas) at his family farm in Andover, New Jersey, with the likes of Malcolm Cowley, William Carlos Williams, Ralph Ellison, Marianne Moore, and many other famous writers and critics of his day.”

In 1941, the major British poet W.H. Auden said Burke was “unquestionably the most brilliant and suggestive critic now writing in America.”

The major American poet, William Carlos Williams, from Rutherford, NJ, corresponded with Burke for 42 years, frequently visited the Andover farm, and wrote of one such visit in the poem “At Kenneth Burke's Place.”

Burke wrote poems, short stories, a novel, music reviews and, mostly, literary criticism. He created a mountain of scholarly texts on the great literary works, exploring the symbols, the historical and personal contexts, and the motives of the writers. He developed methods of criticism, which led to theories on art and politics, and on understanding humankind and life itself. Shakespeare said “All the world's a stage.” Burke said, life is drama. He developed dramatism, a communications theory that examines an individual life like it is a drama, with action, scenes, agents, agencies and purposes. Such an approach allows for discovering what our true motives may be. He asked the deep questions, like What is Man? And he answered. Man, he said, is a symbol using (or symbol misusing) animal. Literature, he said, was symbolic action, and language itself a mode of action.

“My father produced a massive amount of work,” said Burke's son, Anthony, at a recent interview at the Andover house. “There are all the books and papers here. And there are all the materials at the Penn State library. People ask how he ever produced so much. Well, he worked.”

Anthony Burke — a professor of Astronomy at the University of Victoria, British Columbia — indicated a spot in the parlor near the stove.

“That's where his desk was, and his typewriter. He'd sit there eight hours a day, often longer. And work.”

He lived like a recluse, but he wasn't an escapist. His critic's eye was very much on the world.

For example, he recognized that Hitler's methods were a modern threat to democracies. The Rhetoric of Hitler's 'Battle' — Burke's analysis of Mein Kampf — was published in 1939; after the appeasement at Munich, but before the invasion of Poland and the start of World War II. He characterized Hitler as a “snake oil salesman,” a phony medicine-man, and said that it would benefit us to “discover what kind of 'medicine' this medicine-man has concocted, that we may know, with greater accuracy, exactly what to guard against, if we are to forestall the concocting of similar medicine in America.”

Burke said that Hitler held to a four-step formula throughout Mein Kampf and his subsequent rise to power. First: Hitler took the religious idea of inborn dignity and perverted it to inborn superiority for the white or Aryan peoples, thereby making every other people inferior. Second: Among these “inferior” races, he singled out one people, the Jews, who could be made into a common enemy, a scapegoat, upon whom all bad could be blamed and all hatred directed. Third: He promised rebirth, a return to better times, for his followers if they worked to destroy the common enemy. Fourth: He sold his program as a “noneconomic interpretation of economic ills.” In other words, it was not unfair taxation, or corporate consolidation, or international finance that was causing the common man problems — it was those conniving Jews.

Burke is not completely forgotten. University courses in literary analyses and rhetoric still use his work. Blakesley said scholars are “keenly interested in his work on the rhetoric of war and the rise of fascism in Europe prior to WWII.” Blakesley and his colleagues have put together a documentary on Burke, titled Word Man, to be released next year. The Kenneth Burke Society offers writing by him and a video interview by his famous grandson Harry Chapin. His books are still out there, including a collection of his fiction titled Here and Elsewhere. And there's that haunting song performed by Chapin. In Williams' poem, At Kenneth Burke's Place, the poet, who loved to use simple, concrete images to evoke thought on greater matters, speaks of a “small green apple” he spied there. “Bite into it,” he wrote. “It is still good.”

Remember Kenneth Burke.